Top Radon Sources in Homes: Soil, Water, and Building Materials

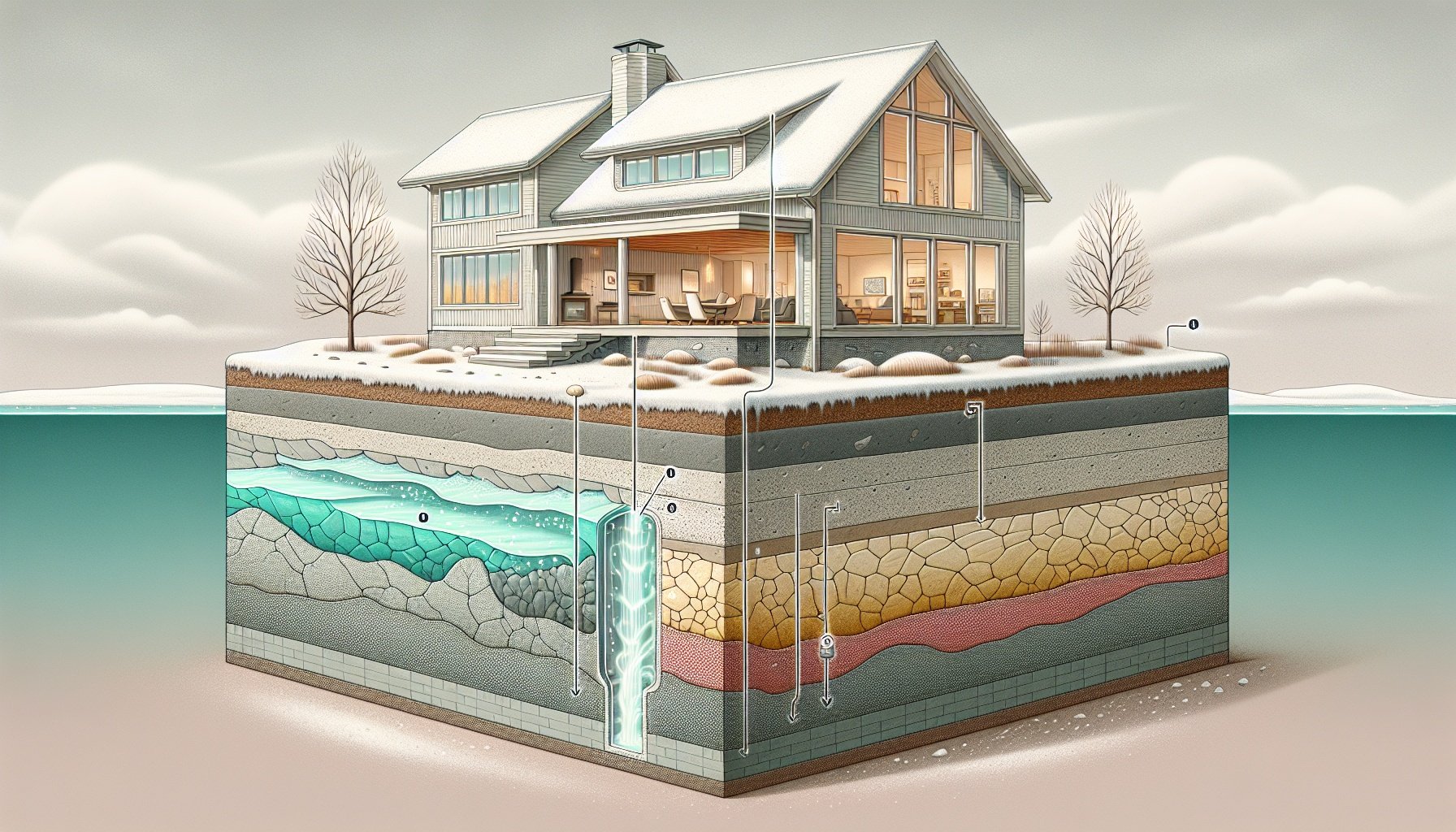

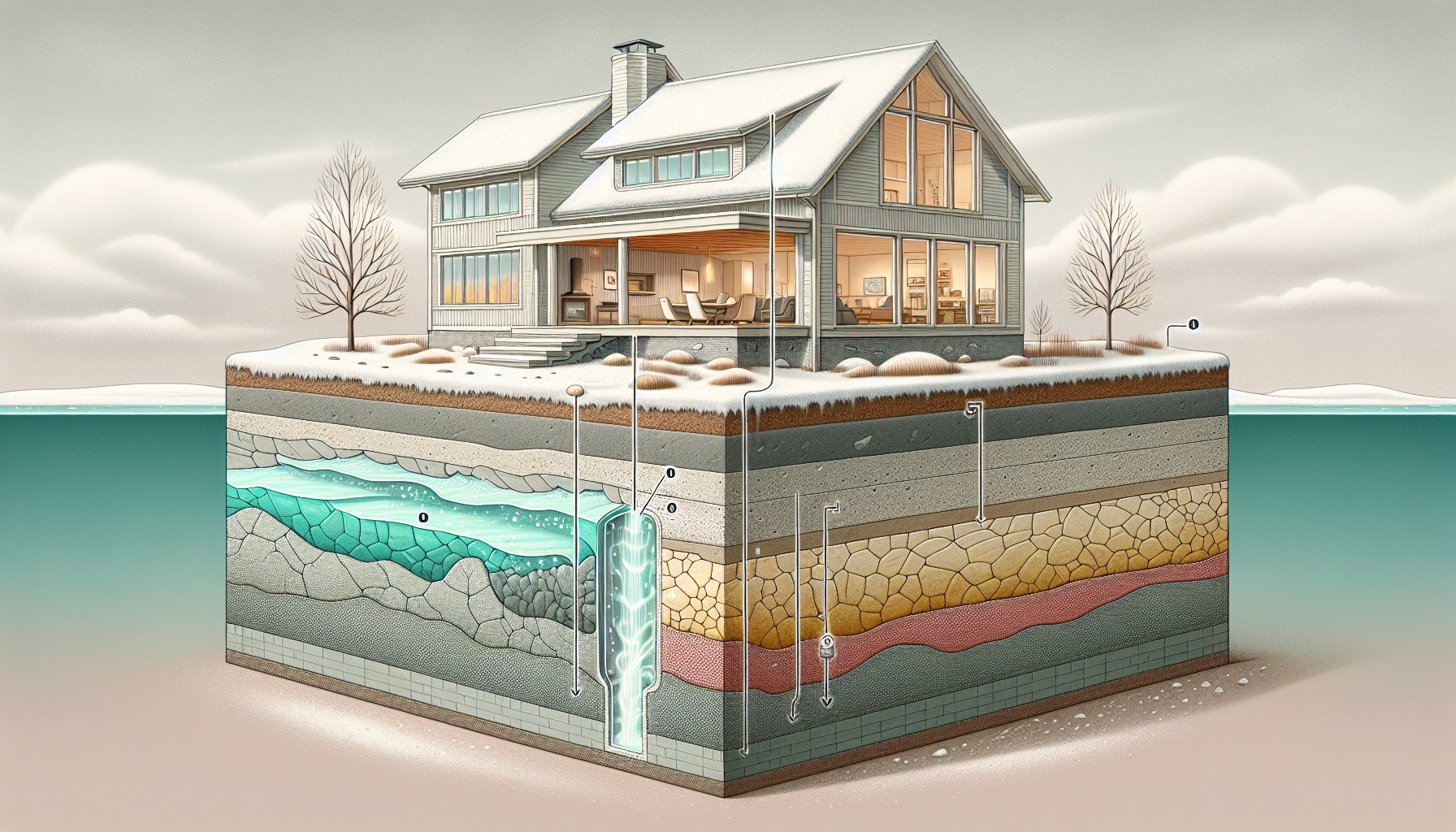

Radon often moves silently through a home, completely unseen and without any smell, yet it remains one of the most common indoor air concerns across Central Louisiana and beyond. This naturally occurring radioactive gas forms deep in the ground as uranium in rock and soil breaks down, then rises toward the surface, searching for the easiest path inside. Soil beneath slabs, crawlspaces, and footings becomes the starting point, but it is not the only way radon finds its way indoors. Groundwater from private wells, especially in rural areas, can carry dissolved radon that escapes into the air during everyday use. Even sturdy materials like concrete, brick, and gypsum-based products can add a low, constant background level over time.

Quick Navigation:

Radon from Soil and Rock Beneath the Home | Radon in Well Water and Plumbing Systems | Radon from Building Materials and Home Components | Frequently Asked Questions

Homes near the Red River, properties tucked against the Kisatchie woods, and older neighborhoods across Central Louisiana often sit on mixed layers of sand, clay, and weathered rock that can allow radon to move and collect under foundations. When combined with tight construction, enclosed basements, bonus rooms, and complex plumbing runs, small sources can add up and create higher indoor levels. Understanding how soil, water, and building materials each contribute to radon exposure builds a clearer picture of where problems start and how they grow. With that foundation, every crack in a slab, every well system, and every wall surface begins to tell part of a larger story about the air breathed every day inside the home.

Radon from Soil and Rock Beneath the Home

Among all potential entry points, soil gas beneath the slab or crawlspace usually drives most radon found indoors. Pressure differences between indoor spaces and the ground pull this gas upward, especially during cooler months when homes stay closed and heating systems run. Even tiny foundation gaps, hairline cracks, or openings for pipes and utility lines can act like small chimneys that draw radon inside. Different soil layers, from loose sand to compacted clay or fractured rock, change how easily the gas travels and concentrates. These hidden pathways and ground conditions shape how radon builds beneath a home before finding a way inside.

How radon forms in soil and moves through Central Louisiana’s sandy and clay-heavy soils

Radon starts as uranium locked inside tiny grains of sand, silt, and clay. As uranium and radium break down, radon gas forms between soil particles and inside pore spaces. In Central Louisiana, mixed sandy and clay-heavy layers shape how that gas travels. Loose, sandy zones around the Red River and older terraces let radon move quickly through open air pockets, almost like smoke drifting through a screen. Clay-rich layers act differently, holding moisture and slowing gas flow, but also trapping radon beneath slabs and footings until pressure pushes it toward foundation cracks. Where sand lenses sit on top of tight clay, radon can build up under homes, then follow utility lines, drain lines, or small gaps straight into living spaces.

Keep in Mind: In 2024, a Harvard study estimated that nearly 25% of the U.S. population lives in homes exposed to high radon levels from geological sources, highlighting widespread residential infiltration.

Common entry points: slab cracks, crawlspaces, sump pits, and utility penetrations

Radon from soil tends to follow the easiest paths into living spaces, and small openings around the foundation act like vents for soil gas. Hairline cracks in concrete slabs, gaps where the slab meets foundation walls, and joints around garage floors all create thin channels that pull radon inside as indoor air warms and rises. Crawlspaces with bare or loosely covered soil act like open radon reservoirs, especially when floor framing above has gaps around plumbing and ductwork. Sump pits and French drains can behave like direct chimneys from the gravel layer under a slab. Utility penetrations for water lines, gas lines, sewer pipes, and electrical conduits often leave small, unsealed spaces where radon-rich soil gas can steadily leak indoors.

Local geology and high-risk locations around the Red River, Kisatchie area, and older neighborhoods

Local geology around Central Louisiana shapes where radon problems show up most. Sandy and silty river deposits along the Red River can allow soil gas to move quickly under slabs, especially near low-lying, floodplain streets and older riverfront neighborhoods. In the Kisatchie area, fractured sandstone, iron-rich soils, and exposed rock outcrops can hold pockets of uranium and radium, creating small “hot spots” where radon release is stronger than surrounding land. Older neighborhoods across Alexandria, Pineville, and nearby towns often sit on mixed fill soils from past construction, with buried debris, broken clay drain tiles, and loose backfill around basements that let radon escape more easily into homes, especially where foundations have settled or been patched over time.

Radon in Well Water and Plumbing Systems

Beyond gases rising from the soil, hidden radon sources often ride straight into a house through its plumbing. When groundwater is pumped from deeper bedrock aquifers, radon can travel inside the well, collect in pressure tanks, and then release at faucets, showers, and laundry equipment. Hot water use and strong water pressure can speed up this release, turning a quiet plumbing system into a steady indoor radon source. Older well systems, unvented storage tanks, and tightly enclosed utility rooms can all influence how much radon escapes from water into the air, setting the stage for several key problem spots.

Worth Noting: Well water containing dissolved radon from underground aquifers contributes to indoor air levels when used for showering or cooking, with concentrations varying by local geology.

Source: World Health Organization

How radon dissolves into groundwater and enters private wells and rural water systems

Radon from uranium-bearing rock and sediments can dissolve directly into groundwater as it moves through tiny fractures and pore spaces. Cold, low-oxygen water holds more dissolved radon, so deep bedrock aquifers, common in many rural areas, often carry higher concentrations than shallow surface supplies. Private drilled wells that tap confined or fractured rock layers pull this radon-rich water straight into homes and small community systems. When water is pumped, stored in pressure tanks, or sprayed through faucets, showers, and irrigation heads, the dissolved radon quickly escapes into indoor air. Rural systems without aeration or treatment let this gas transfer happen unchecked, turning everyday water use into a steady indoor radon source that adds to soil gas entry.

Quick Insight: Modern homes increasingly incorporate sub-slab depressurization systems to actively vent radon gas from soil beneath foundations, reducing indoor accumulation by up to 99%.

Release of radon from water during showering, laundry, and kitchen use

Daily water use creates many small “radon release events” that steadily add to indoor air levels. Hot showers are usually the largest contributor because high temperature, strong spray, and enclosed stalls strip dissolved radon from water very efficiently. Steam and fine droplets carry radon into the bathroom air, where it can quickly reach higher concentrations, especially in homes with poor exhaust ventilation. Laundry can also be a major source, as washing machines rapidly agitate and aerate large volumes of water, pushing radon into the air of utility rooms and nearby spaces. kitchen activities such as running the dishwasher, boiling water, and using the sink for long periods release additional radon, allowing repeated low-level bursts that spread through open-plan living areas.

Interesting Fact: January 2025 marks National Radon Action Month in the U.S., promoting community awareness and testing initiatives to address radon entry from natural ground sources in residences.

Key factors that increase radon in water: well depth, bedrock type, and older plumbing setups

Several physical features of a water system strongly influence how much radon ends up in the water before it reaches indoor taps. Deep drilled wells that tap confined aquifers often intersect more fractures in rock, giving groundwater extra contact time with uranium-bearing minerals and raising radon levels compared with shallow dug wells or springs. Bedrock geology also matters: granites, shales, and certain metamorphic rocks typically release more radon than sandstones or unconsolidated sands and gravels, so wells in those formations tend to be higher-risk. Older plumbing setups can compound the problem, especially long runs of metal piping with many joints, dead-end branches, and unvented pressure tanks that allow radon-rich water to stagnate and release gas gradually into basements and utility rooms.

Radon from Building Materials and Home Components

Soil gas and pressure differences tend to drive most radon indoors, but the house itself can quietly add to the problem. Building materials and common home components sometimes contain tiny amounts of uranium or thorium, which slowly break down and release radon over time. Concrete, brick, natural stone, some types of gypsum products, and even certain tiles or countertops can all act as low‑level radon sources. Individually, these materials usually give off small amounts of gas, but in tight, energy‑efficient homes those emissions can still matter. Different materials, finishes, and fixtures each play a role in how much radon they add to indoor air.

Concrete, brick, and block walls as minor but steady background radon sources

Concrete slabs, brick veneers, and concrete block walls often contain trace amounts of uranium, thorium, and radium in the sand, gravel, and cement used to make them. As these elements decay, radon gas forms inside the material and slowly diffuses out into indoor air. This release is usually low compared with radon entering from soil or well water, but the surface area is large and the emission is continuous, creating a minor yet steady background source. Basements and first floors with exposed block or bare concrete surfaces tend to show slightly higher contributions, especially in tightly sealed homes. Dense concrete, solid brick, and good wall coatings or finishes help limit how much radon escapes from these structural components.

Expert Insight: Geographical variations in radon sources show higher concentrations in homes built on uranium-rich granite soils in regions like the Appalachian Mountains and parts of the Midwest.

Gypsum products, stone countertops, and reclaimed materials with trace radioactive elements

Gypsum drywall, joint compound, and some plasters can contain very small amounts of naturally occurring radionuclides from the original rock or industrial by‑products used in manufacturing. Most modern gypsum products contribute only a modest background radon level, but large surface areas across entire walls and ceilings allow steady, low emissions over time. Stone countertops add another specialized source. Granite, some darker quartzites, and stones with visible veins or specks can hold trace uranium or thorium, releasing both radon and direct gamma radiation, though levels vary widely by quarry and batch. Reclaimed materials, such as old industrial tiles, antique glazed brick, mine tailings used as fill, or repurposed stone slabs, can carry higher, less predictable radioactivity and sometimes become localized “hot spots” inside a home.

Pro Tip: Radon gas originates from the natural decay of uranium and radium present in soil, rock, and water, seeping into homes through cracks in foundations and walls.

Home design details that affect radon buildup: tight construction, additions, and enclosed basements or bonus rooms

Home layout and construction details influence how much radon from building materials and soil actually builds up indoors. Tight, energy‑efficient envelopes with advanced air sealing reduce natural air exchange, so even small radon releases from concrete, drywall, and masonry can accumulate instead of diluting. Additions such as sunrooms, enclosed porches, or over‑garage apartments often sit over mixed foundation types, creating complex airflow paths and hidden junctions where radon can collect and slowly leak into living areas. Fully enclosed basements, theater rooms, and bonus rooms above garages or sealed crawlspaces often have limited ventilation, heavy use of gypsum board, and large concrete surfaces, turning them into radon “traps” where background emissions from building materials combine with soil gas entry and linger at higher concentrations.

Conclusion

Radon is a naturally occurring radioactive gas that can seep into homes from the soil beneath foundations, making soil gas the primary source of indoor radon exposure. Tiny cracks, gaps, and utility openings let that soil gas move inside, especially where local geology allows radon to build up under slabs and crawlspaces. Radon is also carried in well water drawn from deeper bedrock aquifers, then released indoors through faucets, showers, and laundry equipment. On top of that, common building materials and home components can add small but steady amounts of radon to indoor air. Together, these sources shape overall exposure levels. Regular testing and timely mitigation offer a simple, powerful way to keep indoor air cleaner, safer, and more comfortable for everyone.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is radon and why is it found in so many homes?

- Radon is a colorless, odorless radioactive gas that forms naturally when uranium in soil, rock, and water breaks down. This process happens almost everywhere on Earth. When radon is released from the ground into the open air, it usually spreads out and does not reach high levels.

Inside homes, radon can get trapped and build up. Cracks in slabs, gaps around pipes, and openings in foundations allow radon from the soil to enter basements, crawl spaces, and lower floors. Modern homes are often tightly sealed to save energy, which can reduce fresh air exchange and allow radon to accumulate indoors.

Because it cannot be seen or smelled, radon goes unnoticed without testing. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and health agencies recognize radon as a leading cause of lung cancer among non-smokers, which is why its presence in homes is taken seriously.

- How does soil under and around a house become a major source of radon?

- Soil is the main source of radon in most houses. Natural uranium in the ground breaks down over time and releases radon gas. This gas moves through tiny spaces between soil particles and follows the path of least resistance.

Under and around a house, several conditions can pull radon from soil into the structure:

– Air pressure differences: Many homes have slightly lower air pressure indoors compared to the soil around the foundation. This pressure difference works like a weak vacuum, drawing radon from the soil into the house through openings.

– Foundation openings: Small cracks in the foundation slab, gaps along the footing, expansion joints, open sump pits, unfinished crawl spaces, and spaces around plumbing and utility lines create entry points.

– Soil type and moisture: Loose, dry, and sandy soils allow radon to move more easily than dense, wet clay. In Central Louisiana and similar regions with mixed soil types, changes in moisture after heavy rain or drought can change how quickly radon moves.Because soil is present under almost every building, it usually becomes the primary source of indoor radon unless strong secondary sources, like radon-rich water, are present.

- Can well water or other household water sources contribute to radon levels in a home?

- Water can be a secondary source of indoor radon, especially in homes that rely on private wells drawing from groundwater. When groundwater flows through rock and soil that contain uranium, radon can dissolve into the water.

During everyday activities such as showering, doing dishes, running laundry with hot water, and using faucets, radon in water is released into the indoor air. While most of the health risk from radon comes from breathing the gas, some risk also comes from drinking water containing radon.

Public water systems that use surface water (like lakes and rivers) usually have very low radon levels, because radon escapes into the air before treatment and distribution. Groundwater systems and private wells, especially in areas with uranium-rich geology, can see higher levels.

Testing both indoor air and well water in areas with known radon potential gives a clearer picture of the total exposure from water as a radon source.

- How do building materials like concrete, brick, or stone become sources of radon?

- Some building materials can release small amounts of radon because they contain naturally occurring radioactive elements such as uranium, thorium, and radium. These materials often come from rock or mineral sources and can include:

– Concrete and cement blocks

– Brick and certain types of clay products

– Natural stone such as granite or shale-based products

– Gypsum-based materials and some manufactured stoneAs these materials slowly break down on a microscopic level, small amounts of radon gas can be released into indoor air. In most standard homes, the amount of radon coming from building materials is minor compared with radon entering from soil.

In rare cases, certain high-radium materials or imported products can contribute more noticeably, especially in very tight buildings with limited ventilation. Overall, while building materials are recognized as a possible radon source, soil gas infiltration remains the main concern in the majority of homes.

- What parts of a house are most likely to have higher radon levels and why?

- Lower levels of a house typically show the highest radon levels because they sit closest to the soil, where most radon originates. Several areas stand out as common hotspots:

– Basements: Concrete slabs are often in direct contact with soil. Any cracks, control joints, or gaps along the walls and floor provide entry points for radon. Finished basements with limited fresh air can trap gas more easily.

– Crawl spaces: Exposed soil or thin plastic barriers in vented crawl spaces can allow radon to move into the air under the floor. That air can then seep through gaps around plumbing and floor penetrations into the living areas.

– Slab-on-grade areas: Homes built directly on a slab without a basement can still draw radon through cracks in the slab and joints where the slab meets the walls.Upper floors usually measure lower radon levels because the gas becomes more diluted as it rises and mixes with indoor and outdoor air. However, air flow patterns, heating and cooling systems, and closed Windows and doors can all affect how radon spreads through the structure.

- Do seasonal changes or Louisiana’s climate affect radon levels inside homes?

- Seasonal changes and local climate can strongly influence indoor radon levels. Several factors come into play:

– Temperature and heating: During cooler months, houses in Louisiana and across the South are often closed up more tightly. Heaters and ventilation patterns can create stronger pressure differences between indoors and soil, which can pull more radon inside. Measured radon levels often rise in winter and fall for this reason.

– Air conditioning and sealed windows: Long, hot summers lead to heavy air conditioner use. Windows stay closed to keep cool air inside, which can reduce natural ventilation and allow radon to build up.

– Rain and soil moisture: Heavy rain common in Central Louisiana can temporarily change how radon moves through soil. Saturated soil can push more radon sideways under slabs and foundations or, in some cases, reduce soil gas flow if pores fill with water.

– Wind and storms: Strong winds and storm fronts moving across the region can change air pressure inside and outside a house, affecting how fast radon is drawn from the ground.Because of these shifts, long-term radon testing that covers different seasons provides a more accurate picture of average exposure.

- How can common entry points for radon be reduced to lower indoor levels?

- Reducing radon from known sources usually focuses on blocking entry points and safely venting gas from beneath the structure. Common steps include:

– Sealing foundation cracks and gaps: Filling visible cracks in slabs, sealing around utility penetrations, and closing gaps at wall–floor joints can cut down on soil gas entry. High-quality caulks and sealants designed for masonry or concrete give better, longer-lasting results.

– Improving crawl space barriers: Covering exposed soil with thick, sealed plastic sheeting and closing unnecessary gaps can limit radon entry from under floors.

– Sub-slab or sub-membrane depressurization: Professional radon mitigation often uses a fan and vent pipe system that draws radon from beneath the slab or crawl space lining and exhausts it safely above the roof. This method directly targets soil gas before it enters living areas.

– Addressing radon in water: For well water with high radon, systems such as granular activated carbon filters or aeration units can reduce radon before it reaches faucets and showers.

– Maintaining balanced ventilation: Proper ventilation, sometimes with dedicated fresh-air systems, helps dilute indoor radon and maintain more stable air pressure.Each house has unique entry points and conditions, so radon testing followed by a tailored mitigation approach usually achieves the most reliable reduction in radon levels.